Blog #7/21 Care-giving and Care-taking

By Savina Petkova

The co-s of that night stood out as an overwhelming statement of the need for togetherness. Amidst collaboration, communications, constellations, and consolations, a more vowel-y, albeit slightly shorter word rolled off the tongue often enough to change the rhythm: care. Is a cinema of care possible, or is film merely there to dress the wounds?

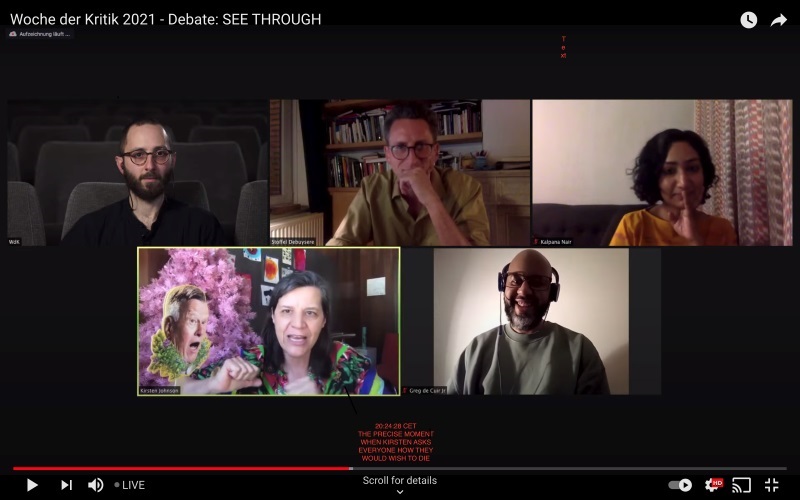

Amidst the Berlin Critics’ Week, another meeting of festivals took place – that of Mumbai Film Festival and Courtisane – to unearth the ebbing currents of intimate hardships in a radically gentle way, within a program titled See Through. Opening the floor, notably without the directors of neither shorts nor feature film, four panelists first addressed the absence in question, and did so as the ever-structuring lack (rather than death), that of the author. The curators present – Kalpana Nair, Greg de Cuir Jr., and Stoffel Debuysere – unanimously appointed the physical presence of filmmakers at events as an audience-pleasing aspect to festivals that has proven to be a fickle challenge because of the financial abundance it entails. Director Kirsten Johnson, on the other hand, admitted to a human-all-too-human desire to endow the filmmakers in question as particularly apt examples of professionals going at great lengths to, as she put it, find filmic solutions to impossible situations. The longing for one’s presence was thus rendered tangible as the absence itself, yet all three short films shown (Foyer, Oumon, and This Day Won’t Last) gifted the viewers with hauntingly intimate confessions, all resorting to allegory and/or repetition as an aesthetic (ergo political) necessity.

The spectral presence of an achingly physical reality was, therefore, a constant companion to the themes that came up, whether inspired by the short films, or by Farida Pacha’s full-length documentary Watch Over Me. As such, the erosion of presence, already evident in any cohabitation or collective, was often drawn out to reach its earthly limit: death. A conversation that spun between the reality of death and the responsibilities of both filmmaking and curatorial practices, the debate itself strayed away from any remedial remarks, while also refusing to assume a prescriptive role, even if it was expected: curators procure, and filmmakers make it “better”. Acutely conscious of contextual specifics of the films and one’s own individual prompts to relate to them, Johnson was the first one to articulate a feeling of displacement that would summarise both the spectatorial experience and the personal engagement with the films.

How do we watch films now? And, more importantly, how do we watch the tough ones? Curiously enough, the question, as it stood today, had turned from “Is this film worthy of me?” to “Am I worthy of it?” In a similar manner, these questions can also be condensed to a tentative “Am I able to?”, which already undermines any spectatorial reliability and signals towards a paradigmatic shift, accelerated by our socially distant, pandemic times. Instead of a communal experience, installed in the seats of Hackesche Höfe Kino, each and every one was given the freedom and trust to organise, and, thus, recontextualise their own viewings. This program in particular, being what can generally be considered “a touch watch”, has presented itself as an assemblage that allows for re-programming possibilities and modes of engagement characteristic of the shifting locus of power relations. Greg de Cuir Jr. used the playful term “asymmetrical collage” to gesture towards the horizontal relationality between (two or more) screens, and between spectators and screen alike.

But still, there was something unspoken, and, thus, imminent. Upon confronting a program as saturated with impending death and danger as this one, I realise that it taps precisely into the kind of fear one ought to keep repressed in order to go on with their daily lives. (Wo)man cannot live in a Sein-zum-Tode state, one can only die as such, so what else are we always trying to avoid? Halfway through these musings, Johnson’s grounds me, as I catch the end of her sentence: “…have you thought of how you wish you’d die?” Most surprisingly, at the breaking point, everyone’s smiling. Much like the discussed episode by the end of Watch Over Me, when a terminally-ill patient smiles with relief, after he had finally decided to return to his village, and die. Let it be said, there is not a single trace of cynicism, but such a question, even suspended in mid-air, has opened up space for shared (and maybe sought after) intimacy. Any possible answer matters way less than the act of being confronted with the idea itself, in its imminent presence. Collective vulnerability, or a constellation of grief – the togetherness exhibited in those two seconds of smiling silence taps into the possible impossibility of all the films discussed. Whether it’s the white sheet of paper in Foyer, or the claustrophobic closeness to people’s deathbeds, the notion of excessive intimacy hovers over cinema’s (always deferred) wake.

Representing death is probably the longest standing taboo of cinematic practices. Excluding death from its morbid, irrational, titillating qualities and rejoining it with the banal truthfulness of human life is something reminiscent of contemporary turns in philosophical thought, mainly uptaken by feminist ethics in relation to care. In formulating her ten propositions on death, representation, and documentary, film theorist Vivian Sobchack was very careful to include a clause that postulates the viewers’ own responsibility for their visible visual response. The act of looking itself can hold one accountable, and this is the flip side of voyeurism (and imagine if we, viewers, thought we could get away with it). The judgement, which one spectator or curator might bestow upon a filmmaker who has filmed in risk or around death, already implicates the viewer or speaker themselves. Filmmaking should, therefore, be equated with moral conduct: we have to, at all times, and even more so in cinema, include the other in the consent.

The latin word for care is cura, from which curation takes its name. But doesn’t the act of caring (and curating, for that matter) imply that someone is sick (an audience question voiced in the Berlin Critics’ Week Telegram chat, only not “live”)? Does it not proliferate the selfsame power dynamic that is rigged as binarisms of any kind are – the ever-hungry desire to consummate the weak under the false pretense of salvation? “No, it’s more about care for the filmmakers,” another chat message pings, and one cannot help but feel the encroaching presence of Michel Foucault or Jean-Louis Baudry, both sounding the bell of dispositifs that determine our viewing practice and environment, dissolving. At least that’s one ghost we can dispense with, together.

Care-giving and care-taking are not and should never be thought of as transactional. Making care apparent, on the other hand, is what cinema can do, is what filmmaking and curatorial practices are fit to do in the ripeness of their political symbolism. At least their deaths will be delayed.

A video of the debate can be found here. The conversation “Filmmakers Talk Back” with the filmmakers of the short film programme can be seen here.