Blog #3/21 The Mountain, the Activist, and the Médiathèque

By Irina Trocan

Filmmaker Francina Carbonell made a factual statement ripe with implications when asked about the source material of her film The Sky Is Red in the Berlin Critics’ Week first debate, Facing Traces. She was able to obtain police evidence regarding the San Miguel prison fire in 2010 because, by Chilean law, evidence in public trials is publicly available. However, this straightforward answer eludes the most valuable aspect of the film – its ability to build a case using information hidden in plain sight about the institutional neglect that led to the prison tragedy that left 81 inmates dead.

The trial established that prison authorities are guilt-free, despite the obvious delay with which the Fire Department was alerted and the multiple testimonies that inmates were not sheltered from the expansion of the flames. It is quite common to our digital age for the abundance of audiovisual content – of institutional mishandling, of #BlackLivesMatter-protest-sparking atrocities, of public misdeeds and gruesome propaganda of any sort – to be more widespread than somebody’s availability of searching through this mass of possible leads. Whatever evidence such footage or documents might offer, it takes an intelligent and perseverant spectator to sift through them, and the effort ought not to be understated. Halfway through the debate, Austrian filmmaker Ruth Beckermann inadvertently highlighted the relevance of Carbonell’s project in narrating the event to a wider audience by recalling how vaguely she had heard of the San Miguel prison fire – in the European press, it was one of many headlines of a tragedy (taking place in a “far-off country”, to paraphrase the other title from Monday’s programme).

Accessibility in an essay film’s language became an inevitable topic of the debate. The Sky Is Red seeks to resonate in viewers’ minds by bringing up the globally widespread issue of inadequate prisons, whereas Suneil Sanzgiri’s more circumlocutory film Letter From Your Far-Off Country riffs on cultural inclusiveness and diasporic identity with a dizzying degree of formal play. Sanzgiri’s personal stance on whether the film should be fully comprehensible to viewers outside South Asia is a fairly determined “no”. After screening his film to international audiences, he serenely concluded that some viewers are determined to look up missing references regarding Indian activists and catch up with what the film communicates about the Kashmir conflict. Thus, the freshness of its form may persuade some to become engaged with the film’s topic, which is more than what we can say about so many conventional and exposition-ridden documentaries.

With the participation of curator Dennis Vetter and moving-image scholar Volker Pantenburg, the discussion progressively elucidated both selected titles and the similarities between them, as well as the filmmakers’ intentions and techniques while working on them. It occasionally veered into downright cinephile coinage of unmade film; at one point, Sanzgiri conceptualized a parallel, more visceral telling of the San Miguel fire, where the time passing as we view the film – roughly equivalent to the excruciating hour when flames engulfed the prison under the inmates’ powerless gaze – is painfully felt.

Should these films be deemed politically engaged? Sanzgiri, for one, uses computer-generated imagery (be it a virtual landscape or anthropomorphic), the dissonant recitation of an Agha Shahid Ali poem, physically pasting saffron on the 16mm film stock (obtained from transferring a desktop documentary to analogue, no less), family connection with an Ambedkar scholar, Google Street View-like imagery and footage, or robot replicas of the country’s dissidents from several decades ago. (While this might sound unappealing in a plain text enumeration, the film is much richer and visually fascinating. Thankfully, we owe it to the opening conference of Berlin Critics’ Week to establish Incoherent Cinema as a badge of honour.) Sanzgiri’s approach is perhaps too personal or eccentric to resonate widely, let alone to make spectators’ blood boil and get them to protest on the street, but it is political activism – or at least outspokenness – that his short’s protagonists all have in common, and the work gives it a subtly heroic glow.

Harun Farocki’s spirit floated over the films as well as the debate, and his name was mentioned before Volker Pantenburg (author of Farocki/Godard: Film as Theory) even got his turn to speak. Carbonell’s project brings to mind Farocki’s Prison Images (2000), a visual investigation into how incarceration is mythologised that also acknowledges prison cameras have a more precise and powerful role than merely recording and later representing events. In at least two instances, The Sky Is Red is strongly reminiscent of Prison Images. Shortly after the fire spread in San Miguel, someone from the prison staff effectively blocked a camera by repeatedly zooming in to a nondescript, random spot on the ground. In a broader sense, there is the perpetual incompleteness of images, which only become less oblique, in the absence of text explanations, by corroborating them with each other, and thus allowing them to also expose anything fabricated that does not fit into the previous pattern.

The sheer spatial familiarity with the prison, which Carbonell’s work eventually produces, through prolonged accumulation of visually similar footage, is a more subtle, non-humanist endeavour for building empathy that at the same time precludes viewing this prison fire as an isolated case. The subject under scrutiny is not this particular prison, this particular unfortunate event, this one particular malicious guard who wouldn’t unlock the door in time, but an entire system that is rigged against the inmates’ human rights.

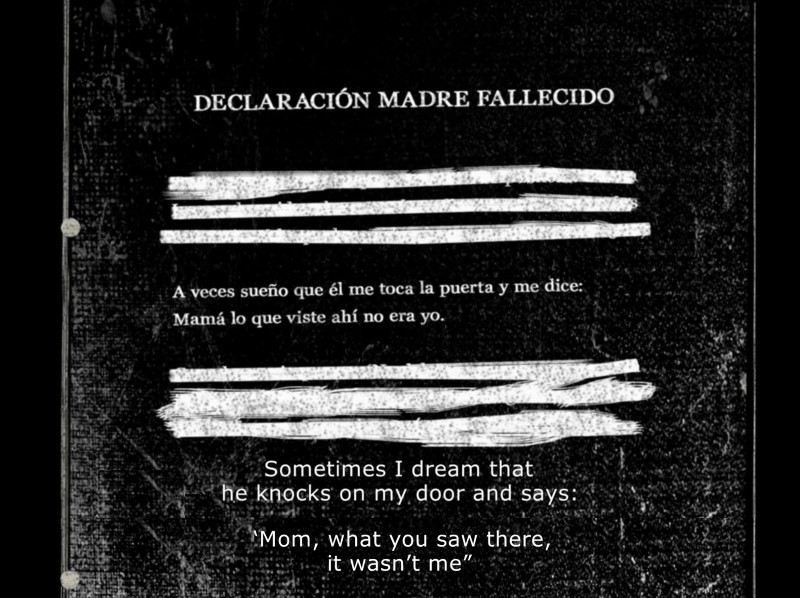

By the end of the film, viewers are so immersed in active observation, so finely attuned to speculating on what went on, that one minor detail, such as the hesitancy in the guard’s voice when phoning in with an emergency – and later the passivity in meeting the operator’s feckless response – registers fully. Somewhat antithetically to the very personal Letter From Your Far-Off Country, here the filmmaker’s involvement is minimized, despite Carbonell’s account in the Critics’ Week discussion of how she kept in touch with the victims’ families. There are fleeting hints of her emotional involvement, such as including the transcript of a testimony in which the mother of one of the inmates confesses to an eerie dream – her son appears to tell her “Mom, what you saw there, it wasn’t me”.

Even from a wider perspective than this already globally relevant subject, The Sky Is Red shouldn’t need teary interviews and ticking clocks to resonate. After a full year of mostly poorly timed lockdowns and inefficient safety measures, many people’s trust in institutions is at an all-time low. Nursing homes become SARS-CoV-2 hotspots overnight, hospitals are overcrowded, and patients die not just of COVID, but of occasional hospital fires. Is this post-pandemic turmoil a good moment to count on the audience’s understanding and hope for a significant change in society? Sanzgiri and Carbonell are not exactly euphoric in foreseeing the future (Carbonell mentioned that prison reform isn’t any politician’s most beloved cause), but hopeful nonetheless. Among the scenes from Sanzgiri’s film that panelists kept referring to is actress Shabana Azmi’s détournement of a conventional, self-promotion festival Q&A: rather than answering how she works with various directors, Azmi used the occasion to announce an activist’s unacknowledged death to the festival audience. Berlin Critics’ Week guests remarked that the speech is longer and more coherent, with no interruptions, than one would expect of this gesture of guerrilla activism. Yet maybe the opportunity to be outspoken in the midst of complacent socializing is not such a rare occasion, after all.

A video of the debate can be found here.