Blog #5/20 – Peering in from the Fringes

By Caitlin Quinlan

To open the Berlin Critics’ Week evening on the 25th February, host and moderator Dennis Vetter began with a quote from filmmaker Luise Donschen (unable to be present for the screening) that read, “Intimacy is a state of deepest connection that knows nothing of the possibility of its violation.” With the evening’s title, “Collapsing Distance,” already in mind, the session commenced with a strong suggestion of what was to come, and Donschen’s quasi-proverb would go on to provide a series of curious and challenging readings of the films presented.

Donschen’s film Entire Days Together, all primary colours and windswept trees and flowing water, preceded the monochrome tones of Valentina Pedicini’s sect-focused documentary, Faith. They presented a stark contrast at first glance in both aesthetic and tone, but there are almost amusing similarities within the works that the filmmakers themselves had only begun to notice during the session and subsequent debate. Both films use stroboscopic light, for example, or seem to be more focused on the stories of the female characters present in the work. Both films also feature scenes of people brushing their teeth and going about their daily tasks. Importantly for the topics of discussion set out in the event title, both films share a reliance on closeness and distance albeit in their own different ways.

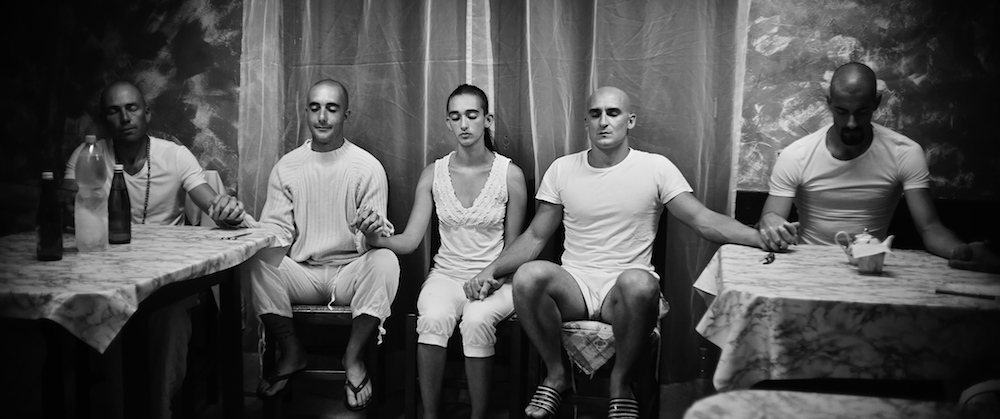

To make Faith, Pedicini and her cinematographer Bastian Esser spent five months partially living with a Catholic-cum-Kung-Fu sect community in Italy where a “Master” figure guides his disciples in martial arts training and religious piety. They live in a community that holds no value in privacy, sharing all aspects of their lives in what is at once a display of their intimacy collectively and a violation of any individual intimacy. The very presence of Pedicini and Esser is possibly a violation of the community’s intimacy itself. Still, Esser’s camera denies distance in near-permanent close-up, a closeness that invites us as audience to recognise the threat in what we’re viewing and understand also how bodily control is crucial here.

Where Faith allows its subjects to fill the distance between observer and observed with their own existence and narrative, Entire Days Together is a more romantic evocation of community and individual expression. A school, almost its own neighbourhood, is the focus, a place where young people with epilepsy and other disabilities are educated and supported. Donschen and cinematographer Helena Wittman keep their framing tightly controlled, and in one beautiful moment of simplicity we see the girl at the heart of the film floating in a swimming pool. She drifts into frame and out again, her limbs only just slipping back into view while the camera remains still. In another film we would track her movement, but here the static frame gives her the freedom to escape our gaze. “Intimacy allows for borders,” Wittmann said in the discussion that ensued, a poetic insight into the emphasis and direction of a work that encourages distance to create closeness.

There were many areas of interest in the debate following the films, although somewhat understandably due to its raw, intensified energy, Faith was the work that seemed to take up most of the oxygen. Audience fascination with the subject of cult or sect is clear—perhaps it’s the idea of our distance but ever-potential closeness to such a lifestyle that intrigues us, keeps us peering in from the fringes to scope it all out. Distance was discussed by the panel as a mode of enchantment, whether films “change” or “transport” them, suggesting that distance can be challenging and that the active participation required to challenge it is crucial to the experience of cinema.

Pedicini was asked by guests Karim Aïnouz and Mathieu Landais about her focus on the suffering of the women in the community; the tortured believer Laura, the nervous young mother, and another girl pushed to her limits. “This is a film against the patriarchy,” Pedicini explained, noting the distance she had to create for herself as a female director in order to deny the Master his power. “In this film, he loses.” A similar idea motivated Esser’s choice for black and white, as it allowed him a personal distance to a dark world he could not see in colour.

In Entire Days Together, however, Wittmann uses her camera to express her feeling of emotional proximity even in physical distance. It’s a mode of observation that allows the poetics of sensation, movement, and tactility to collapse any alienation we may feel from a lack of narration but still maintain a sense of liberty. In Faith, denying the audience distance carries a political weight so that the activities of the community do not go unchallenged, whereas Donschen’s film searches for freedom in distance for its burgeoning youth.