Blog #2/16 - Radical Acts of Memory

by Richard Brody, movie editor at The New Yorker

Notes on a screening of Coma

Chantal Akerman died last October, soon after the première of her last film, “No Home Movie,” in which—using a small video camera to create images of an impressionistic mystery, she films her aged and ailing mother, who talks about the family’s experiences in and after the Second World War. Akerman is irreplaceable, but her spirit lives on in Sara Fattahi’s film “Coma.” Did the young director see Akerman’s film? It doesn’t matter; the artistic spirit isn’t transmitted by immediate contact but through the force of ideas that an artist puts into the world through work, and that can be passed along to another creator as if carried in the air.

Filming—or, rather, video-recording—her mother and grandmother in the family’s apartment in Damascus, Fattahi experiences life in wartime and films it as she experiences it. She hasn’t made a documentary about the war in Syria; she has made a film about herself and her family, about their lives in the present tense and the infusion of memory, of personal memories and cultural memories from which their lives today are constructed.

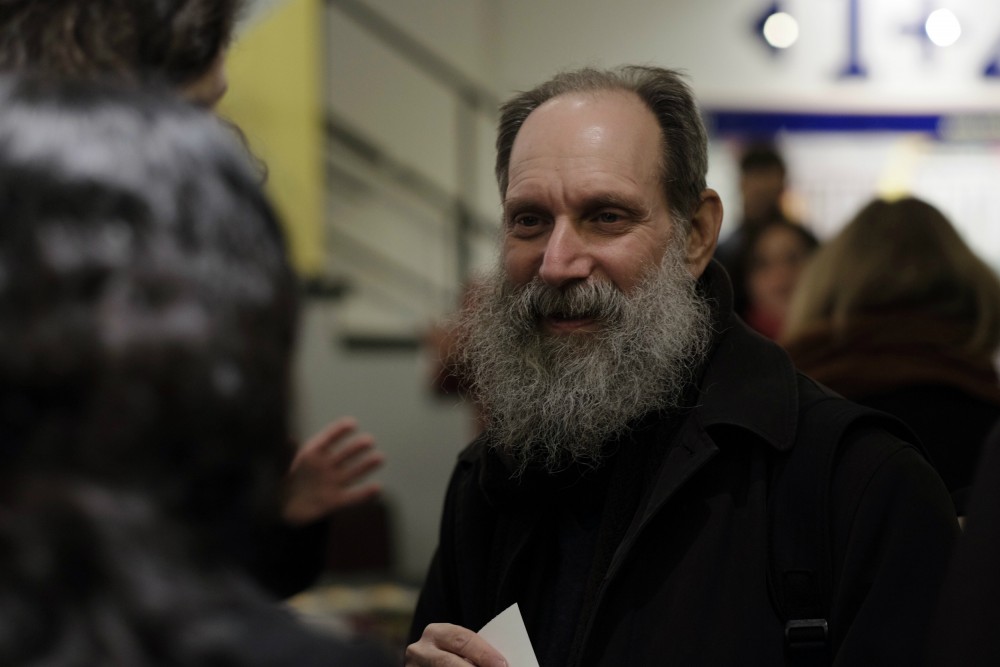

The discussion that followed the screening, between Heba Amin, Fadi Abdelnour, Jay Weissberg, and the moderator, Joseph Fahim, was centered on the representation of war—and, in particular, on the proliferation of documentary images of victims, of atrocities. The panelists agreed that, by their number and ubiquity, these images lose their specificity and their immediacy and become neutered objects in a media landscape—they lose their power to shock and even to inform. And they agreed—and I agree with them—that Sara Fattahi’s film “Coma” is an active and creative form of resistance to media overload and media oblivion.

Fattahi doesn’t film what’s happening “there” in Damascus but what’s happening “here” in Damascus. She’s not filming life during wartime in Damascus in any abstract sense but her own particular experience, joined to that of her mother and grandmother in their apartment, of this war in this city at this particular time. And she’s not filming with apparent consciousness of a particular audience which she’s trying to inform or motivate, but of her own urgent necessity to create a work of art, a work of cinema, that embodies her experience.

In “Coma,” Fattahi offers not the objectivity of facts about which she asks us to trust her authority (although the film is rigorously attentive to the actuality of what’s taking place in her presence) but an artistic creation in which her own aesthetic sense, the authorship of her style, is itself the nature of her authority. In discussing the representation of war, the panelists alluded to the problem of efficacy—of whether filmmakers have a responsibility to create images that are intended to make a concrete difference in raising the consciousness of viewers regarding the political events being filmed. Heba Amin answered that the artist’s main responsibility is to her own personal and emotional imperatives, drives, necessities, desires. I agree with her—and would add that any real efficacy in art comes not from the fulfillment of a sense of responsibility but from an artist’s power to create.

Fattahi’s resistance to the flood of media representations of war isn’t editorial or doctrinaire, it’s immediate, personal, and emotional. “Coma” doesn’t reflect a mission but a passion. All great political documentaries are also radical acts of memory; “Coma” takes its place among them.

Where do ideas come from? No filmmaker can think in the abstract about viewers in the abstract. They think about their experiences, about their emotional responses, about their ideas, about what they imagine, and they create work that will echo in the soul not of a collective of viewers but of individuals—maybe many, maybe even just one. But that one person may vibrate intensely with another power, one that carries the artist’s ideas into other dimensions, and then, the work of art is in the air and may be carried—even to many people who haven’t seen it and may never see it—further into the world at large.

Just as Akerman’s films have inspired Fattahi whether or not she has seen them (the very notion of direct influence would be interesting to know about but is inessential), so Fattahi’s film, though it will likely be seen not by a mass audience in the most prominent media platforms, will be passed along, not only intentionally, like a secret disclosed privately from friend to friend with the confidence of revelation, but also implicitly, like a frequency that someone far away, who is in tune with her, will pick up and amplify.

In Jean-Luc Godard’s film “Every Man for Himself,” the character Paul Godard, a filmmaker and teacher played by Jacques Dutronc, discusses Marguerite Duras’s film “The Truck” with his students. He says that, after seeing the film, “Every time you see a truck pass by, think that it’s a woman’s speech that’s passing.” After seeing “Coma,” every time I see a curtain blowing in the breeze, I will think of a woman in war.