Blog #6/18 - Humor and Fragility

by Steve Macfarlane

As a first-time Berlinale attendee, I was honored to be invited to Woche der Kritik for a double feature on “humor and fragility”. The audience guffawed throughout Quebecois filmmaker Olivier Godin’s surreal, low-budget whimsi-comedy Attendant Avril, while Serge Bozon’s Madame Hyde – a restaging of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde within the Parisian public school system, and a savage parody of prestige films about teachers inspiring their pupils (French and otherwise) – slowly sapped the merriment from the room as the clock approached midnight. The films were well-matched: Attendant Avril was my first Godin, but its low-budget, makeshift magic-realism formed a nice inverse to Bozon’s fastidious, Old Hollywood-indebted polish. Because I vastly preferred Madame Hyde, the double bill meant reckoning with my own preferences and prejudices, specifically on the item of comedy – which, per the original prompt, indeed requires and/or exposes an emotional investment from the viewer.

Bozon and Godin were both joined for a panel discussion with film critic Ekkehard Knörer and The Forest For The Trees actress Eva Löbau, who cited Peter Sellars’ classic (and painfully dated) comedy of social humiliation The Party. She pointed out that humor is always an essentially inter-relative process, and it can’t happen without some schadenfreude (my word, not hers), a process of humbling on either side of the screen. I then remembered something a professor had called the “Homer Simpson principle”: when it happens to you it’s awful, but when it happens to somebody else… it’s comedy.

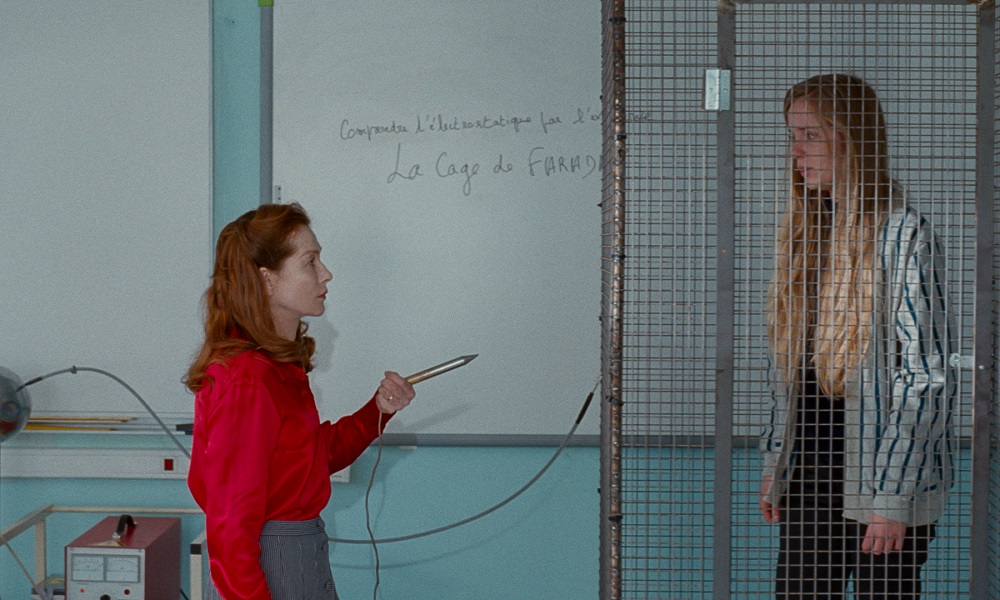

Along with clever, feces-obsessed wordplay (all nonsense-speak) Godin’s film seems to coast on this discrepancy: the narrative (?) follows a female police detective named Haffigan (Johanna Nutter) and an actor reeking of shit (played by François-Simon Poirier) – which is to say they are both in a continual process of being humbled. Bozon uses schadenfreude as a jumping-off point to explore a variety of issues within 21st century France: Madame Hyde stars Isabelle Huppert as one Mrs. Géquil (Jekyll), a high school physics teacher who’s a bit of a pill, and whose palpable dissatisfaction with her lot in life dictates her relationship to her bored and rowdy students, the majority of whom hail from the immigrant communities of the “suburbs” of Paris.

Bozon described the disjunction in France between “technical” (engineering, etc) and “general” (humanities, etc) education as a prejudice in French society, but as I recall many English-language critics found the race politics of Madame Hyde problematic last year. This prompted another question: how much background knowledge should be required to “get” a joke? If a syllabus is required, can the teller be sure it really “works”? Just as a great work of art must refuse to let both maker and consumer off the hook, Godin’s film sees that everyone takes the piss: in one scene, Haffigan calls a hair salon that serves black women only, and claims to be black – to which the woman on the other end of the line replies by telling her she has a beautiful accent.

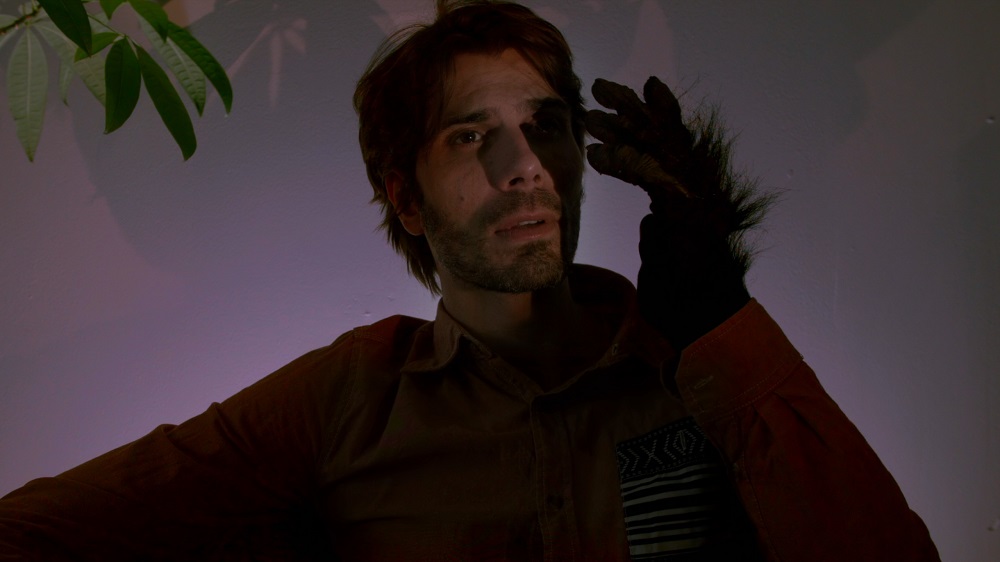

Godin spoke of inventing things on the spot, including my favorite gimmick of Attendant Avril’s, a repeated iris-out that involves a hand closing in front of the camera’s lens – in reality it was the filmmaker’s, wearing gloves patterned after the hands of a gorilla (a recurring motif in the film.) During the salon-appointment scene he said he mixed the music high enough to mask the audio of him laughing behind the camera; Bozon rerouted the conversation back to golden-era Hollywood, explaining that his hero John Ford would regularly begin his films with a comedy sequence as a way to settle the viewer in before throwing them off-guard later. I was heartened by Knörer’s willingness to tell Godin that he didn’t laugh during Attendant Avril but that he recognized its humor: the film with more laughs had less to say about the world, while I could see the Bozon as impenetrable. In my experience, comedies are the hardest films to argue for. Structure, form, performance and text can be debated in words, but it’s worth remembering that the subjective nature of an easy laugh varies wildly between viewers. First as tragedy, second as farce – although on the night of this event, the order was reversed.